The Case Against Legacy and Donor Admissions

For decades, DC’s highly selective private universities have admitted student bodies that overrepresent White and wealthy students and underrepresent working-class, first-generation, and minority students. At the core of this problem is admissions preference for the children of alumni and donors, two groups that are disproportionately White and wealthy. By continuing to offer a substantial boost to these applicants, Georgetown and GW are making it that much harder for students from underrepresented communities to win admission.

And that matters far more than people realize. Alumni of DC’s universities disproportionately go on to join the economic, political, and cultural elite. By shutting the door for students from underrepresented backgrounds, these universities will make it harder for these communities to gain access to wealth and power.

But steps can be taken to change this reality. We must start by ending admissions practices that work against equity, starting with legacy and donor preference.

Argument Overview

What are Legacy and Donor Preference and Where Did They Come From?

In the 1920s, America's elite private universities concentrated in the Northeast had a problem. The long dominance of White Anglo-Saxon Protestants in their admissions classes was being eroded as Jewish and Catholic applicants began to win admission in greater numbers. Fearing they would lose access to these universities and thus their control of politics and society, the Protestant families that governed these schools realized offering admissions preference to the children of alumni would boost Protestant applicants and punish Jewish and Catholic applicants. Thus, legacy admissions was born.

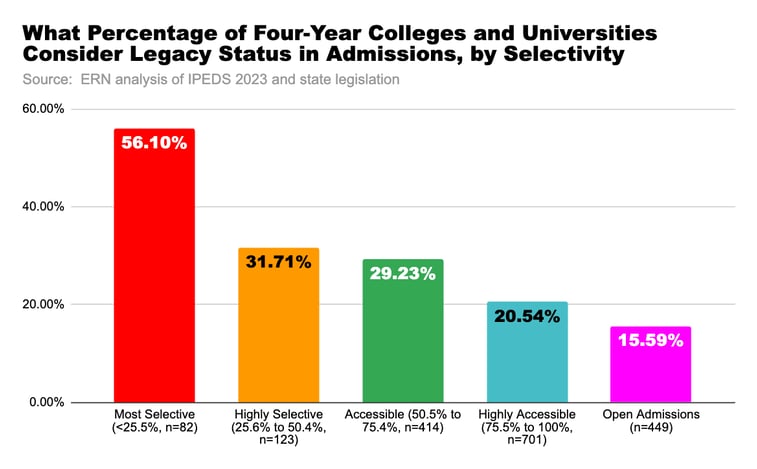

Since then, legacy preference has spread to universities across the country. But in recent years, legacy admissions has finally begun to decline in prominence and, today, the number of four-year colleges that consider legacy status is at the lowest its been since the data was collected. American University, for example, ended the practice after the affirmative action decision. But, in DC, legacy preference is still practiced at Georgetown and GW, and across the country, the wealthiest, most exclusive universities are the most likely to continue practicing it.

While the Department of Education does not require disclosure like they do for legacy admissions, preference for the children of donors is also a widespread admissions practice. Georgetown, for example, practices legacy and donor admissions in tandem, with the largest admissions boost going to the children of alumni who have donated. In December of 2024, a new legal filing also revealed that Georgetown's president submitted a secret list of students from ultra-wealthy families to the admissions office every year without regard for the student's academic qualifications. On the list, he wrote "Please Admit", and almost every student on the list was.

How legacy preference is practiced varies at every university, but Georgetown offers one of the most egregious preferences of any university in the country, with legacy students admitted at double the rate of non-legacies. In fact, 10% of each incoming class at Georgetown is reserved for legacy students. At GW, legacy students are admitted at 1.5 times the rate of non-legacy students, as they pick legacy students whenever they have to choose between two equally qualified students.

A Crisis in Diversity

Georgetown and GW have consistently failed to enroll classes that reflect the racial and socioeconomic diversity of college-goers nationwide.

Socioeconomic Diversity

Georgetown and GW like to claim that they enroll qualified students from all backgrounds, but the truth is their students overwhelmingly come from wealthy families.

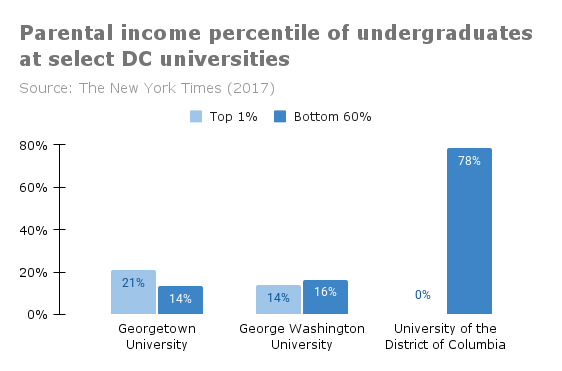

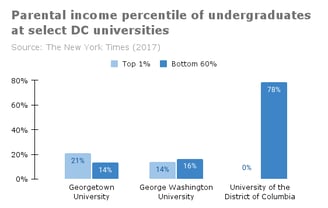

These schools' striking lack of working-class students is matched by the overwhelming presence of ultra-rich students on their campuses. At Georgetown, there are more students who come from families in the top 1% of the income scale than the bottom 60%.

At GW, there are about as many students from the top 1% as the bottom 60%. Contrast that with a school like the University of the District of Columbia, which enrolls 0% of its students from the top 1% and 78% from the bottom 60%. It's clear who these universities choose to serve and, more importantly, who they choose not to.

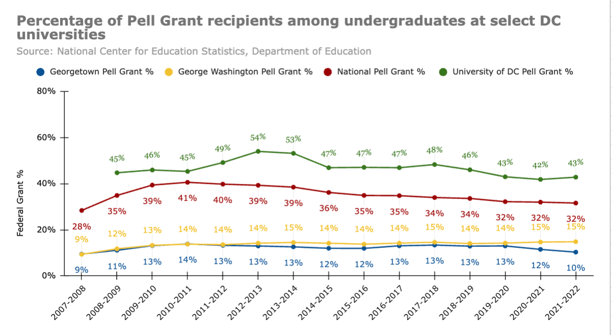

Both Georgetown and GW for years have under-enrolled Pell Grant recipients, students who generally come from the bottom 50% of families by income. In fact, both schools have enrolled lower than half of the national proportion of Pell Grant recipients in their student bodies since 2007.

Racial Diversity

Georgetown and GW's persistent lack of socioeconomic diversity is matched by their decades-long struggle to enroll classes of students that proportionally represent Black and Hispanic students.

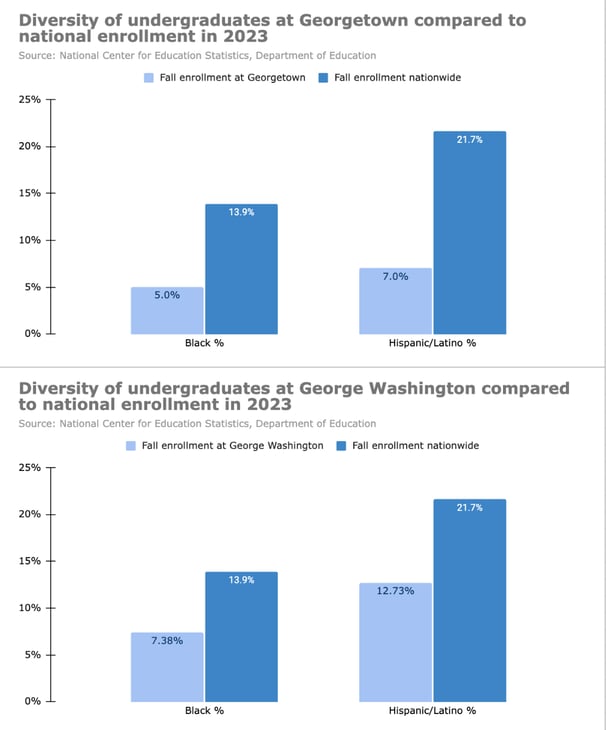

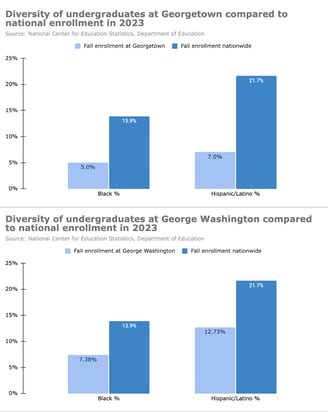

When we compare these schools' enrollment of Hispanic and Black students to the national level, their lack of racial diversity and representation is made clear. At Georgetown, 5% of students are Black, while 14% of students are nationally, and 7% of Georgetown students are Hispanic or Latino, while nearly 22% of students nationally identify as such.

GW is slightly better at enrolling Black and Hispanic students but still severely under-represents both groups, with 7.4% of GW students identifying as Black and 12.7% identifying as Hispanic or Latino.

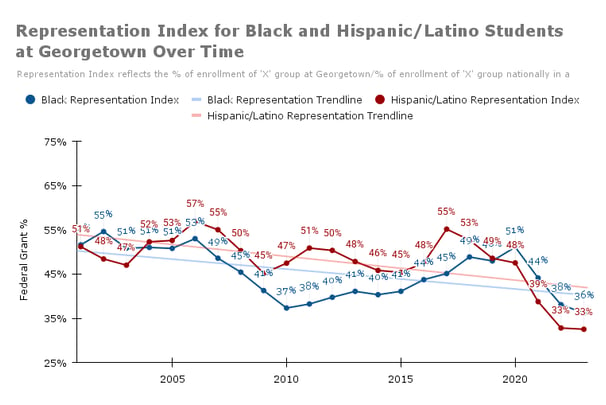

The most troubling finding in our research though is Georgetown's tumbling representation of Black and Hispanic students. We use a representation index to measure how well-represented Black and Hispanic students are as a proportion of their national enrollment. To create this metric, we just take the enrollment at Georgetown of 'x' group divided by the enrollment of 'x' group nationally.

The data shows that Georgetown has seen its representation of both Black and Hispanic/Latino students fall by roughly 20% since 2001, indicating that Georgetown's enrollment of Black and Hispanic students has failed to keep up with national growth. Worst of all, there were fewer Black students at Georgetown in 2023, than there were in 2001.

How Legacy Admissions Discriminates...

Georgetown's and GW's struggle with diversity can be directly tied to their admissions practices. The pool of legacy students is overwhelmingly white and wealthy. By boosting the application of these students over others, Georgetown and GW punish working-class students and students of color.

....Against Working-Class Students

...Against Students of Color

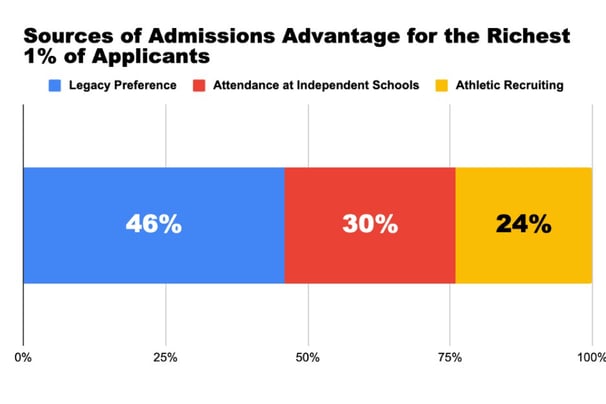

It's no accident that these campuses are dominated by wealthy students. Georgetown and GW's admissions policies directly boost the application of many students from the highest income levels. At both schools, an applicant from the top 1% is nearly three times more likely to win admission than an applicant from an average income background with the exact same test scores and academic qualifications

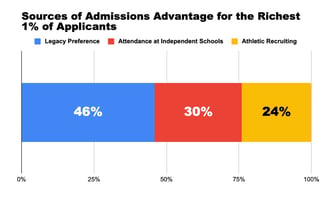

Economists at Harvard and Brown identified three reasons for the advantage the top 1% students enjoy. The most significant explanation was the preference that universities offer to legacy students, accounting for nearly 46% of the boost.

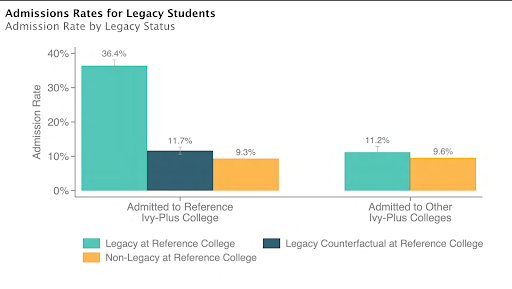

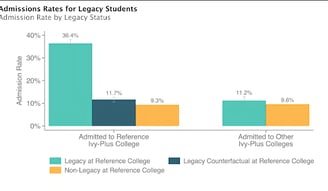

These economists also found that, at the average Ivy-Plus college, legacy students were over three times as likely to be admitted at a school where they have legacy status than an equally exclusive school with no legacy status.

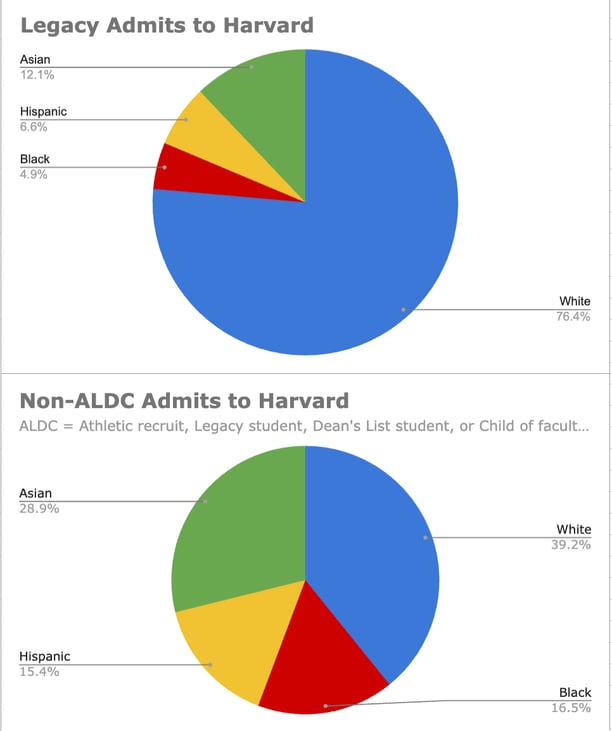

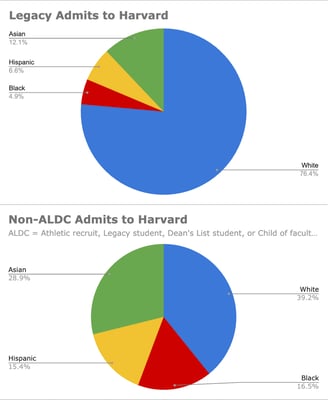

Because of the long history of racial discrimination and exclusion in college admissions, the pool of legacy applicants is overwhelmingly White.

For example, when many of today's legacy parents were graduating from Georgetown in 1989, Georgetown was 80% White. Today, it is only 42% White.

Unfortunately, we can only get a sense of what the legacy pool looks like from these numbers, as Georgetown and GW refuse to disclose the diversity levels of their legacy students. But one thing we do know, at institutions with a better history of representation and inclusion than Georgetown and GW, the legacy pool is still overwhelmingly White.

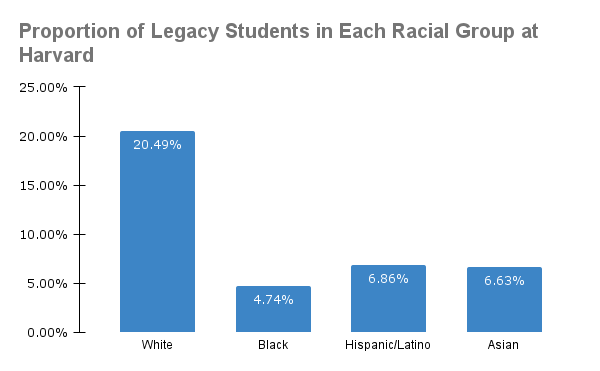

At Harvard University, the only school recently forced to disclose the diversity of their legacy and non-legacy pools, legacy students were nearly twice as White as the pool of students who didn't benefit from an admissions preference.

That data also showed that at Harvard, 20% of White students benefit from legacy admissions, while only 5% of Black students, 7% of Hispanic, and 7% of Asian students do.

A separate study with a focus on Asian-American applicants confirms these numbers showing that White applicants were three times as likely to have legacy status as Asian applicants.

But perhaps most importantly, Georgetown's own education experts were asked to write a report on how the university can protect enrollment for students of color if affirmative action were struck down. Their number one recommendation was eliminating legacy admissions.

If they want to protect racial and socioeconomic diversity, Georgetown and GW must start by ending legacy and donor admissions. Short of that, it is incumbent upon the DC government to intervene to protect opportunity for their constituents and ensure that the hundreds of millions of tax dollars they give Georgetown and GW every year does not go to fund outright discrimination.

Our bill, the Furthering Admissions Inclusion and Representation Act, does just that. Ending legacy is not a silver bullet solution to the problems of opportunity and representation at these schools, but it is the best first step that can be taken to protect diversity from the fallout of the affirmative action decision.

Why It Matters Who Goes to These Schools

Whether you like it or not, when Georgetown and GW make an admissions decision, it has disproportionate consequences for us all. Students at America's most-selective, private universities, like Georgetown and GW, disproportionately go on to become Presidents, members of Congress, Fortunate 500 CEOs, Rhodes Scholars, and other elites. They are also much more likely to go on to attend elite graduate schools and join the top 1% of income-earners.

The truth is the Georgetown admissions office doesn't just pick the next class of Hoyas, they play a heavy-hand in picking the next generation of America's leaders. That's why it's so important these opportunities go to a diverse array of qualified applicants from all backgrounds, especially those traditionally under-represented in the highest levels of our politics and culture.

But even short of playing a role in deciding the next generation of America's governing elite, Georgetown can play a transformational role in the life trajectories of low- and middle-income students. Economists at Georgetown's independent education research institute, the Center on Education and the Workforce, estimated that forty-years out, a Georgetown diploma has a $3.3 million return on investment for Pell Grant recipients. When the Georgetown admissions office chooses to admit an applicant, they are making a $3.3 million decision.

That's why it should matter to us all what criteria Georgetown is using to pick its incoming students. That's why we should all care about making the admissions system fairer and providing more opportunities to working-class students. That's why legacy and donor admissions must go.

Washington, DC 20057

hoyasagainstlegacy@gmail.com